|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

System Thinking in a Personal Context Farrokh

Alemi, Ph.D.

Chapter 3 in “A Thinking Person’s Weight Loss and Exercise Program”

We acknowledge the assistance of Mary Fittapaldi, who helped us sharpen the arguments in this chapter. Portion of this chapter is based on Alemi F, Pawloski L, Fallon WF Jr. System thinking n a personal context to improve eating behaviors. Journal of Healthcare Quality. 2003 Mar-Apr;25 (2): 20-5. IntroductionEarlier in this book we suggested that weight loss and increased exercise can be accomplished by making systemwide changes and de-emphasizing personal exhortations. Little is known, however, about what is meant by systemwide change, especially in the context of personal change. We tackle this problem here. The chapter lays out ways to distinguish systemic change from personal effort, and provides a case study and numerous other examples to clarify the task of bringing about systemic changes in one’s lifestyle. We and others have used the terms “system thinking,” “system change,” “ecological change,” “environmental change,” “lifestyle changes,” and “structural changes” interchangeably. These words are used often and without a precise definition. Naturally, the first step is to define these terms and to distinguish the changes they describe from change through increased personal motivation, increased effort, and more commitment. We define system thinking—and all related words—as the process of accounting for the influence of various people, circumstances, and historical choices on the behavior we wish to modify. System thinking is the process of understanding how people and circumstances are linked. Many people have heard that they should change their lifestyle but are not clear about what this means or how the change is to be accomplished. We believe that everyone’s life is organized as a system of interrelated events, people, and influences. Making a system change is the same as creating a new lifestyle—these are different words for the same idea.

Individuals are affected more by their own choices than by others. If a person decides to live far away from work and commute, he or she may not be able to exercise as much as he or she wants. Thus one can see that the earlier decision of where one chooses to live or work can affect one’s exercise patterns. System thinking helps to see how earlier choices may limit later options. A key component of system thinking is the recognition of the environment's lasting and silent role in behavior. Every person is affected by his or her environment. Even people who live alone are connected to their environment—and through the environment to other people. Take for example an asthmatic who lives by himself. He may be alone but others still influence his behavior: pollution in the air affects his breathing, which affects his ability to exercise, which affects his metabolism and his food intake. In the end, the very air around him connects him to others and opens him to persistent influences. In our view there is no exception to this rule. All people are linked to their environment and to others. No one is isolated. In this book, we use the concept of system thinking in a personal context. The words personal and system, at first glance, seem contradictory: Personal focuses on the individual, while system implies a world of interacting events beyond the individual's realm of control. Juxtaposing these words helps us emphasize that humans live in a complex mesh of activities. Each activity is affected by the individual’s decisions—and likewise the environment, the system around us, triggers changes in our behavior. It is personal in the sense that it is a unique set of circumstances that we live in and it is a system because it involves others and many factors beyond a person’s control. Alemi et al. (2000) gave a particularly demonstrative example, mentioned earlier in this book, regarding system thinking. In this example, a person opens the refrigerator, pulls out a piece of cheesecake, and eats it. However, this person did not make this decision immediately, or just by himself. Part of the decision to eat the cheesecake was made earlier through previous choices. Where he lives, how often he exercises, how much he works, what he purchases at the store, with whom he eats, and a host of other earlier choices affected this person’s need to eat the cheesecake. Many people might eat the cheesecake and needlessly admonish themselves for failing to stay with their diet. Unfortunately, they are attacking the wrong decision, which may not help in keeping their own resolutions. They should focus on what made their options limited to the cheesecake rather than focusing on the cheesecake itself. System thinking can assist in redirecting our focus to the real problem.

Perhaps the best way to define system thinking is to describe what it is not. We asked a colleague to describe how she loses weight. She gave a description provided in Table 1. If you examine her advice, you see very common themes. You see repeated slogans urging the individual to remain committed. It is as thought the individual has to compel and pressure himself/herself to keep up with a diet or regimen. The vocabulary is one of controlling urges and restricting behaviors. In the end, the person is fighting himself or herself. The enemy is within. The focus is to tame one’s desire. System thinking is different. System thinking is about changing the environment and then letting the new world you have created guide you. When the environment is reorganized, weight loss is not about resisting but accepting and fitting in. Current Approaches Are Not Working

In the United States, billions of dollars are spent each year by individuals trying to lose weight. Yet approximately one in three adults is obese, and overweight and obesity rates are rising. Few solutions appear to have an effect on the spread of obesity. Most medications and surgical procedures are not effective, unless a person adheres to a nutritious diet and incorporates an exercise program in conjunction with these therapies. Diet and exercise regimens are not working as many people cannot keep up with their own resolutions. And while many Americans are careful about reading food labels and purchasing foods that are low in fat and calories, they are still getting fatter. Most of us know what we are doing wrong. We know that large portion sizes are not healthy, we know that snacking often is not good for us; we know that drinking too many sweetened sodas is not reasonable. We know this and more. We know that we do not exercise enough. Though we are aware of the problem, we are unable to solve it. The advice to people who want to lose weight, as noted in this book's Introduction, is straightforward: eat less and exercise more. The controversy arises concerning how to follow this advice. What we do not know is how to keep at it. The real issue is how to lose weight and keep if off, since many individuals lose weight temporarily, only to gain it later. A recent study by Dunn and his colleagues (1999) showed a way out of the cycles of repeated weight loss and weight gain. These researchers demonstrated that obesity management might benefit from a program that emphasizes system thinking and environmental changes. In their study, elderly patients who made systemic changes in their environment had the same weight and health outcomes as patients who actively participated in exercise programs delivered through free gym memberships. This study was particularly important because its two-year follow up period showed a lasting impact of systemic changes. The study thus raised the possibility that long-term weight loss could occur through simple environmental and lifestyle changes without a commitment to rigorous diet or exercise programs. In 2000, we studied how system thinking might help people improve personal habits. We showed that 83 percent of people exposed to ideas behind system thinking (some followed it, some did not) were successful in achieving their resolutions in a 15-week period. The study provided additional data on the importance of an ecological model of obesity and excessive weight. In the previous chapter, “Does It Work?” we provided additional data regarding the experience of nearly 200 participants in our classes. These data show that participants who made system changes in their lives were several times more likely to accomplish their goals. In sum, system thinking might be a solution to a problem that we have not been able to solve for decades. Beyond the Precede-Proceed ApproachApplying system thinking to personal issues is not a new idea. In 1990, Green and Kreuter suggested one of the earliest methods to come out of system thinking principles. They called their approach the Precede-Proceed model, emphasizing that people should look at what precedes a behavior and what follows to understand the barriers and reinforcements. Their approach focuses personal improvements on three key areas:

· Reinforcing factors. Examples include positive comments from friends, data on weight loss, rewards, helping others, and incentives. Clinicians and public health professionals use the precede-proceed approach to understand behavior. We advocate a method of system thinking that goes beyond the work of these investigators. Description of Case StudyTo exemplify how system thinking can be used in a personal setting, we will use a recent case in which a physician taking a course at George Mason University was able to reduce the his junk food consumption by joining a car pool. How could joining a car pool affect one's diet? On the surface, the two seem unrelated. But an analysis of this person’s life established a relationship between these two events. He was able to see that his junk food habit was affected by various work and home habits. Working late, for example, was interfering with his ability to find the time to cook, which led to a counterproductive cycle whose details are provided below and shown in Figure 1. Armed with this kind of knowledge, our student was able to break the cycle and reduce his junk food intake. Joining a car pool, since it had a fixed schedule, forced him to leave work on time. We will use his case to demonstrate how system thinking can bring new insight to people who want to go on diet or exercise regimens. The student in our case study used the steps that we proposed in the workbook (Chapter 1). He selected a team of process owners, set goals that would benefit the entire team, described his personal system of life, polled the team for a list of ideas (making sure these would address the system, not one's own activities), decided to undertake a change, monitored the change by gathering data, and continued to tinker with the system as necessary, all the while keeping his story and progress out there for the team to follow and comment on. Principle 1: Look to the Environment

System thinking starts when a person looks beyond his or her motivation and examines the environment. By environment we mean people and machines and buildings and weather and whatever other factors that might affect diet or exercise. Most people who decide to diet and exercise emphasize their motivation. They come up with resolutions such as the following: I am going to eat less. I am going to count calories. I will follow my diet. I will exercise more. A person can say he or she will do something, and will mean it, yet will not be able to do so. An individual can beat himself into frenzy over a resolution, but unless a positive environment is created the resolution will be difficult to keep over time. A more sustainable approach is to change the environment and search for system solutions—not personal exhortations. When a person emphasizes motivation and willpower he is not examining how the world affects him. Certainly motivation matters, but what makes it remain a constant force and what brings about willpower is the environment. Creating a positive environment can lead to success even if a person is not fully motivated. This type of environment ensures that a person retains healthy habits. In contrast, a poor environment can eventually lead to failure, no matter how hard a person tries. To really succeed, in a way that is sustainable, there needs to be a change in the system. System thinking starts when one seeks solutions and causes in the environment—not in one’s commitment or motivation. Obviously, to change the environment you need to be motivated. But this is a different kind of motivation. When you are dieting by relying on your own motivation, you need to constantly tell yourself what you want, you need to be vigilant and committed, every slip-up matters. When you change the environment, you are still working on your motivation but indirectly. Now the motivation emerges because of the new environment; even if you are not vigilant, it still influences you. So you do not need to remain terribly motivated, the world around you takes care of that. Principle 2: Focus on the “Steady State”

The previous principle emphasized that a system is a wide open concept and entails everything in the environment. But it is not reasonable to try to conceptualize everything, and no one can do so without heroic effort. To say that everything affects a person’s diet is not effective analysis—it's paralysis. We need to simplify system thinking, make it more practical. One way to do so is to focus on recurring routines and events in the environment—not just bad habits but also all life routines. While systems are expansive, one identifiable aspect of a system is that it is an organized structure with recurring characteristics—it is not a random heap of events. Analysts like Feller (1968) refer to these recurring events as the “steady state” of the system. A daily routine can articulate the organizing principles of an individual’s life. By listing these routines, a person can see the steady state for his or her system of life. The process reveals the direction in which he or she is heading (and will continue to do so, if no new influences are introduced). Most people sleep and wake up according to a routine schedule. Even end-of-week socialization and partying follow certain routines. Many events happen periodically—some daily, others weekly, still others with longer periods. A key principle in system thinking is to focus on these periodic events. It is not that non-routine events do not matter—they do. But their effects are unlikely to assist in making permanent changes. One way to examine a person’s daily routine activities is to make a list of periodic events. Table 1 in Chapter 5 shows one such list.

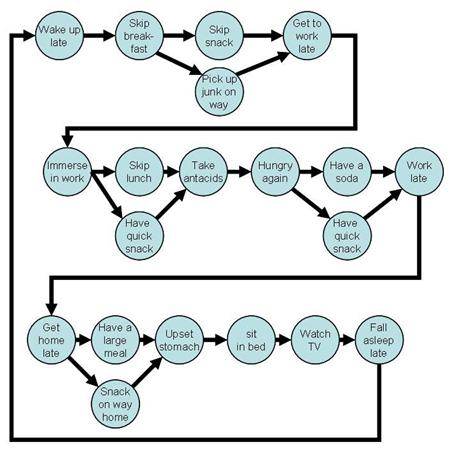

Figure 1: Shopping and Meal Preparation are Related Once routines have been listed, it is important to examine cycles among them. Systems naturally return to their steady state. When life styles are examined, it is important to find these steady states and understand how they occur. Life routines are interrelated. For example, what you eat is related to what you shop for and vice versa (see Figure 1). These linked routines are called cycles and provide the building block of life styles. We can change our lives by changing the cycles among repeating events. Cycles create inertia and resistance to change in the sense that if one element in the cycle is changed, the rest resist the change and encourage return to old habits. So if you change your food habit but not your shopping habit, then the relationship between these two routines encourages relapse to old habits: Old shopping patterns encourage return to old eating habits. In this sense, there is a conspiracy among life routines. They all work together to defeat our efforts to change our life style. They work together to continue current habits. Understanding where life cycles are occurring is one of the first steps in understanding life styles and bringing about lasting change in them. Cycles among the routines are not always apparent. Some are complex and involve several routines. Figure 2 shows the cycle for the case study in this chapter involving work, sleep and eating routines.

Figure 2: A Cycle among Work, Sleep & Diet Routines In the above example, the cycle is self perpetuating. Changes in any element of the cycle will be resisted by others. But if somehow the cycle is broken, as when the person car pools, then all routines are free from the constraints and can be more easily adjusted. Principle 3: Examine Cause and Effects

System thinking requires us to examine the influence of recurring habits on diet and exercise. This is done by parsing diet and exercise into various smaller activities and finding a link between daily routines and these smaller components. In order to exercise, a person must have the ability to exercise and the potential to be healthy, he or she must want to do so, he or she must have the time to do so—and there is often a need to have specific exercise clothes and equipment. There are many factors to consider when trying to eat a healthy diet. For example, to eat healthy one needs access to healthy foods at the right time. To avoid high fat, high-calorie meals, which are available at most fast food joints, a person needs time to prepare his or her meal at home. Finally it is important that individuals eat with friends and family in a setting that is hospitable (rather than alone, parked in front of the television). To understand how daily routines affect behavior, we recommend making a list of what is necessary for exercise or diet. Once the list is complete, it is important to go through each routine and see how it affects the items on the list. Some routines create barriers. For example, working late reduces the time available for exercise or meal preparation. Other routines, such as going to the beach, may encourage diet and exercise. By sorting out how routines affect exercise and diet, an individual can understand what he or she needs to do to change his or her environment. One commonly used method for understanding the relationship among various events is to create flow diagrams of causes and effects (this tool is further discussed in Chapter 5). Figure 3 shows a flow diagram of our student’s daily life routines. The diagram depicts the way the student in our case study perceived how his junk food habit was affected by various work and home habits. Figure 3: Flow Diagram for the Case Study

[edit: bottom row: Capitalize "sit" in "sit in bed"]

Note that the late departure from work is related to late dinner, which is related to failing to fall asleep, which is related to waking up late and getting to work late, which is related to missing breakfast and eating junk food to compensate, which is related to missing lunch, which leads to leaving work late. A vicious cycle is created that continues to feed itself. The flow diagram relates the junk food habit to awakening times, work habits, television-watching habits, and a number of other activities. It helps relay how daily routines are affecting this person’s diet. Principle 4: Change Routines, Focusing on System Solutions

Any systemwide solution to diet and exercise problems involves changes in daily life routines. But not all changes are systemic readjustments. A systemic change can be distinguished from personal solutions in four ways: 1. A system solution affects many others besides the individual. For example, if the system solution is to shop better; it affects everyone at home and not just the person dieting. 2. A system solution often affects one's behavior through a chain of events—some of which are not immediately obvious to an outside observer. A system solution requires the individual to repeatedly ask, “Why is that so?” For example, one may ask why he eats too much. The answer may be because he takes comfort from food. Then he might ask why he is comforted by food and determine that the reason is fatigue. Asking about why he is tired will help the individual see a chain of actions and reactions that ultimately lead to weight gain. Thus, a system solution often involves a chain of events; a personal solution does not. 3. A system solution can be distinguished from personal solutions by who initiates the action. A system solution tends to force the activity on the person and does not rely on the individual’s initiative. 4. A system solution often requires a one-time change as opposed to an ongoing effort. Considerable effort goes into changing a system and finding a new equilibrium for the system, but once changed, the system continues to influence the individual. Often, no new effort is needed. Table 2 shows examples of solutions that are increasingly more system-oriented. Table 2: Solutions Ranging from Personal to System Oriented

In the case study, working late was interfering with finding the time to cook. The solution chosen was to leave work earlier. But this was easier said than done. Sure, our student could resolve to leave work earlier, but sooner or later work pressure would take over and he would begin to leave late again. In the next step we will see how he built leaving work into his routines so that it would occur without his initiative. People who want to apply system thinking should examine the solutions they are promoting to see if they are based on personal effort or systemic changes. The above criteria can help distinguish between the two. In Chapter 1, we provided a questionnaire that could be used to assess the extent to which a change is based on a system solution as opposed to personal effort. This questionnaire is shown in Table 3.

Solutions that require more effort and commitment, do not involve changes in the environment, are not systemwide solutions; they are solutions that rely on increased personal effort and motivation. The purpose of system thinking is to come up with systemwide solutions. System solutions break the cycle of interdependent routines. One way to do this is to analyze routines and embed parts of exercise and diet activities into existing routines. Specifically, the goal is to embed a component of a new habit into an existing routine so it occurs without much effort. The new habit will recur because the routine itself will recur. For example, take the case of a computer programmer who must sit for hours in front of a computer. She may resent the sedentary nature of her work. To solve the problem she can create a standing table so that she longer must sit for hours. She can do most of her work standing and occasionally sit down to relax. In this fashion, the ergonomics of her work changes so that she is less deskbound. By making a physical change in her environment she is able to lead a more active life. This increase in activity is built into her daily work and is automatic. Ironically, this woman initially blamed her lack of activity on her work, but now she is actually more active because of her work. Another example that can assist in increasing activity is to put exercise clothes in the car after the wash. This makes the routine of washing clothes contribute to the ability to exercise. When one has to exercise, it is a lot easier if all equipment needed is ready and in the trunk of the car. Then one can drive to the gym and start without much planning. Sometimes the very fact that your exercise clothes are in the car reminds you and propels you to exercise. Surely these changes seem small at first. Standing up a few more hours a day may seem trivial and having the exercise clothes ready may seem like a small consolation, but keep in mind that these are changes in daily routines. They repeat day after day. Like an avalanche, they start small but over time they may gather strength. Small changes in daily routines can result in big payoffs. Furthermore, the payoff comes not only in the direct benefits that these tasks produce but also in the environment they create. For example, standing up may enable a person to be more ready to leave work and join an exercise class. If in the pull and push of daily events, one is ambivalent about exercise, a small event like having the workout clothes in the car could be the feather that tips the scale. Coming back to the student in our case study: he needed to leave work on time, but it was not enough to have the resolve to do so. He needed to embed leaving work into existing routines. He chose to join a car pool. Because a car pool has a fixed schedule, it forced him to leave work on time. We consider his solution to diet and exercise a systemwide solution because these events would occur independently of his initiative. His friends would show up for their ride at the designated time, whether or not he was ready. When habits are distributed over other activities, the effort becomes easier. Let's take a smoker, for example. If you ask him how difficult it might be to stop smoking, he might reply, “No problem at all. I can stop anytime I want to.” Asking him six months after quitting he might reply, “It was easy. I decided to stop and I did it. It was a snap.” But if you asked him during the time that he is trying to quit, he would give an entirely different answer. He might complain about how difficult it is. He might be short-tempered and frustrated and say that it is the hardest thing he has ever attempted. If stopping smoking and starting exercise, to take two examples, involve a certain amount of physical effort, how is it that at different points in time they seem to involve different amounts of energy? The cynical view is that the required energy level does not differ at all, but that over time we distort the difficulty involved. But this is an unsatisfactory answer as so many people could not all have distorted perceptions. Others may say that overcoming a real chemical addiction is harder at first. Certainly there is some truth to this if we are talking about smoking—but it doesn't apply to the same degree if we are talking of other habits such as exercising. Something else is at work here. We think that habits become easier to maintain because the effort gets distributed into other activities. In other words, the effort to exercise or eat properly seems easier because so much of it is accomplished as part of other tasks. System thinking embeds solutions into other routines, by doing so some of the effort is moved from one activity to another. In the case we have been following, the effort of leaving work on time was embedded into the routine of car-pooling. It was no longer a diet-related activity. When asked if he was dieting, our student replied, “No,” he was merely commuting in a new way. He was not changing his diet. But at the same time he seemed to have effortlessly created more time to cook (and thus avoided eating high-calorie fast foods), found more time to exercise, and was able to go to sleep earlier and get up on time to work. All of this was achieved with almost no effort, it appeared to him. It was considered effortless because the energy expenditure was attributed to car-pooling and not to dieting. Principle 5: More Is Better

The environment is complex and sends many mixed messages to the individual. To change the environment, one needs to make multiple small changes. Once success occurs, it is important to continue pursuing other ways to build the new behavior into various existing routines. We hypothesize that the effect of routines on one another is cumulative. As more and more daily routines point to exercise and proper diet, success becomes more likely. Building more of the wanted behavior into existing routines can lead to easier maintenance of that habit. The secret is to continue searching for system solutions even when the system is effective. When you do this, exercise and diet take a life of their own and become a stable part of daily routines. Even with occasional failures, it is important to continue. The ongoing search for system-wide solutions involves avoiding blaming yourself for occasional lapses. Many people cannot keep up with their own resolutions. There is no guarantee of success. Occasionally there are failures, and when they occur it is important to search for a new change in daily routines. Relying on personal resolve and discipline can deliver a blow to one's morale and personality with every failure, and as a result, sooner or later one may abandon the effort in disappointment and frustration. In contrast, when making systemwide changes, every failure is a new lesson on how various routines are interconnected. It provides us with new insight. Every failure can constitute the seed for a greater effort. Instead of abandoning that effort, one can put energy in prolonging the time between failures. Rather than giving up one's diet, it is important to look at the time between the lapses and see what might influence it. For example, perhaps a person has failed to perceive that she tends to eat out often and she does not have many choices when looking for a place to eat. Keeping a diet in these circumstances would be hard. Yet after discovering how her diet is affected by eating out, she can start to rethink her socialization routines. Impact of System Change

Table 4 shows the data collected by the student in our case study.

In Table 4, the first column represents the number of days. The second column indicates success or failure, and the third column provides the duration of consecutive failures. The table shows that on the first day, the student ate junk food, so in the second column it indicates that he did not succeed. On the second day, however, he did succeed. Failure on the first day is one day of failure. Failure on the fourth day is two days of failure because there were two consecutive days of eating junk food since the last day of success. Figure 3 plots the length of relapse against days since our student started his monitoring. This chart can assist us in understanding whether a person is improving over time. The figure shows how the student fared over 57 work days (roughly three months). The horizontal axis shows the passage of time. The vertical axis shows the number of continuous junk food days. Early on, one can see a number of occasions where day after day he was eating junk food. In one stretch, he ate junk food five days in a row. But as time passes we see fewer lapses. Furthermore, the lapses are of shorter lengths. In the second half of the chart, there is only one day when he ate junk food. Sure, he may relapse from time to time but these occasional lapses are not a return to his days of continuous junk food consumption. Over time, relapses became rare. His joining the car pool helped him avoid junk food. Figure 3: Relapse Chart

DiscussionPeople who diet think of what to eat and what to avoid. They see their eating and exercise habits as their own decision exclusively. When health professionals tell them this is not the case, their first reaction is often one of ridicule. They claim that the professionals are abetting individuals in avoiding personal responsibility. After all, who could be responsible for a person’s actions but himself or herself? Let us be clear here: System thinking does not state that a person is not responsible for his or her actions. Even though the environment influences us, this does not mean we are not responsible for our lives. On the contrary, the environment we select is our choice—at some level that is our true choice. People are responsible for their behavior to the extent that they choose their environment and can modify it. No one acts in a vacuum. Often a person fails to succeed because he or she fails to see how certain actions are interconnected. System thinking makes one responsible for the entire constellation of actions around a behavior, instead of a single eating habit or exercise activity. System thinking allows us to approach weight loss like we would any other problem. It allows us to seek causes and effects and engage in cycles of improvement. There are more than claims of willpower at play here. System thinking forces people to confront and solve the problem of why they cannot maintain their resolutions. It is a statement of obvious fact that a person’s environment affects him or her; and that earlier decisions affect later ones. What many do not understand is how to think about personal systems. We have tried to remedy this shortcoming in this chapter by proposing a method for thinking about diet and exercise that relates these activities to daily routines. The proposed approach is designed to assist a person in targeting factors that influence diet and exercise patterns. The approach emphasizes a search for systemwide solutions instead of personal exhortations. It helps put into place solutions that continue to assist you even when you are not motivated. It helps you to examine how large decisions in life (e.g., where you live) affect diet and exercise. It helps you see how numerous small decisions can snowball into major diet and exercise changes. It aims to open your eyes regarding patterns in activities that you might otherwise ignore. Finally, it helps you build solutions into routines that will force you to implement wanted behaviors. System thinking might be analogous to a kind of pyramid scheme in which a person benefits from his or her deceptions, and the goal is to create schemes that preempt future choices. The beauty of the proposed system solutions is that the more a person does, the easier it becomes. The more integrated the tasks are into existing daily routines, the more automatic the approach becomes, and the less independent effort is needed. If you recall, the student in our case study stated that he did not feel like he was dieting. To him, the change in his diet seemed to have emerged with little effort. He was not running around frenzied and trying to fight his own desire to eat junk food. He ate less junk food with no apparent conscious effort at the time. This process of redistribution can work for most people in making them believe that diet and exercise are easy. It is possible, at least in theory, that one can distribute the effort needed for exercise and diet into so many daily routines that the desired outcomes seem inevitable. The promise of system thinking, therefore, is seemingly effortless diet and exercise. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||