Online Health Records

By Bruce Slater, MD, MPH

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

This presentation will compare the history of paper and electronic

patient records, describe the major elements of the electronic health

record and explain how electronic health records are different to the

paper patient chart

Healthcare lags behind many aspects of our lives in automated

information use. Although computers are used in financial transactions

and clinicians use the web for medical and non-medical information

searching, only a minority of physicians use it for storing records.

Electronic Patient Record or EPR and the Electronic Medical Record or

EMR are two names for a similar concept. Physicians typically talk about

Electronic Medical Records while nurses, public health and more

holistically oriented commentators use the Electronic Patient Record

description.

The Computer-based Patient Record, CbPR or CPR for short is the name

chosen by the Institute of Medicine in it’s landmark report in 1991

promoting the use of computer systems in Health Care. In addition to

medical and non-medical health information, the CPRS incorporates and

enables communication, education, analysis and quality control into a

single comprehensive birth to death nationwide system. Ultimately we

have backed off a vision of a monolithic national system in favor of

many systems hosted by healthcare organizations that are able to

communicate via national standards and information interchange networks.

The missing aspect of patient input is included in the most recent

moniker Electronic Health Record or EHR.

After the rise of the stand-alone personal computer we re-discovered

the power of linking computers together. Instead of linking dumb

terminals to mainframes, we divided the power of the main frame into a

Client-Server pair connected over a Local Area Network (LAN). The client

handles the presentation of data to the user and the Server stores files

and does database lookups and serves the data or results back to the

client for action.

In the ASP or Application Service Provider model, the internet has made

it possible to move even more of the processing to a remote site.

Intended for small scale operations that cannot afford a full

client-server EHR an ASP company will purchase the EHR license, the

hardware and the expertise to it and then offer “slices” of the full

functionality to individual practices. Subscribers do not have the large

up-front costs of the full software license, expensive fault-tolerant

servers and expertise of the full support model. ASP companies can fully

exploit the robust applications by selling 100% of the EHR capacity to

many small users. Properly done the ASP model can be a win for both

subscribers and service providers.

When humans discovered that certain of their group had special powers

to heal the sick and comfort the dying they designated them shaman. All

cultures gave their shaman special dispensation to access intimate

aspects of the human body and use potentially dangerous procedures and

potentially poisonous treatments. Shaman trained apprentices by the oral

tradition to follow their practices. When writing became common place it

still took centuries until written records were kept in hospitals. It

seems we have always been behind the technological time. These hospital

records were kept in ward notebooks and they documented the condition of

patients, results of tests and opinions of consultants for the current

episode of care. For the patients in an early 1800’s hospital, a

physician could look back to previous ward book entries, but records

were not generally organized by individual patients. Florence

Nightingale is credited with keeping patient-oriented health records in

the Crimean War in the 1850’s. As healthcare became more technical and

involved many different specific tests and treatments in the 1950’s,

practitioners began to sort the results by their source. So-called

source oriented documentation prevailed for decades in hospitals and

outpatient records. Dr. Larry Weed promoted the concept of medical

records that guide and teach in what he called problem oriented medical

records. He organized his in- and outpatient notes by the (S) subjective

or historical aspect; the (O) objective observations that were

independent of what the patient said; the (A) assessments or assertions

of diagnoses or problems and the (P) plan both therapeutic and

diagnostic. Using the mnemonic of S.O.A.P. all students have been taught

for the last 20 years to keep records in this problem-oriented way.

Creating this kind of record while listening and examining the patient

enables providers to have a running list of issues that must be

addressed in the visit. Although Dr. Weed anticipated implementing

problem oriented medical record in a computer, ironically the SOAP notes

inspired by him have increased the volume of paper records as well as

inspiring electronic versions. As the paper record becomes more

voluminous and central to patient care the lost and incomplete paper

chart has become a chronic challenge to every health care delivery

system.

Dr. Weed always intended his Problem Oriented Medical Record to be

based in a computer. The linkages between the problem list and

individual problem based progress notes can only be done virtually.

Expecting providers to manually track problem numbers between problem

lists and progress notes has led to incomplete records in almost every

instance. To make this possible Weed created the PRoblem Oriented

Medical Information System or PROMIS. Unfortunately the promise of

PROMIS was not realized. Success depended on a very strict use of rigid

text boxes and required fields. Providers, on the other hand, tend to

talk informally with patients and ideally have patient-centered not just

problem oriented interviews. The rigidity of PROMIS was not well

accepted by practicing doctors and the software never caught on. Another

effort shortly after in the early 70’s was made at the Massachusetts

General Hospital. It was intimately related to the development of MUMPS

(MGH Utility Multi-Purpose System) programming language. Many

applications were developed in this language. The COmputer-STored

Ambulatory Record or COSTAR was one of them. This was very strongly

problem-oriented, used a data dictionary to codify the data that it

contained and had a very sophisticated query generating system to

extract data from the database. In addition, it was public domain.

Unfortunately, it’s strong points also became it’s downfall. Because it

was public domain, no company successfully standardized and carried all

of the variations that became available, into the future. For many years

it was the system of choice for public institutions without a budget to

support proprietary systems. Many COSTAR systems, especially at MGH and

Nebraska have prospered and assisted in patient care for over 20 years.

MUMPS, however, lends itself to spaghetti (or excessively branching)

code which is essentially impossible to maintain by a team of

programmers. As programming languages progressed to 3rd and 4th

generation and true object-oriented approaches, MUMPS usage for new

projects ended. Therefore no new MUMPS programmers are being tutored and

COSTAR is fading after a long and illustrious career.

Practice Partner started life as a DOS-based EMR with a proprietary

database format. It has progressed to a MS Windows interface, and is

available with an Oracle database. It is sold through a national network

and has been around for many years. It uses the typical “tab” metaphor

to mirror the look and feel of a paper chart. This is the same metaphor

that has been used in many EMRs since the windows interface has become

available. Practice Partner has been around long enough for interfaces

to have been built to major national labs. The company leverages the

advantages of a large population of users on the same system to

aggregate clinical data and form a research network. They also offer

benchmarking services between and among the large population of users.

They have developed web access to their product, a patient portal and

have offered it as an ASP solution. Medicalogic is another system

founded and programmed by a physician and born as a DOS program. It is

now available as a client server Oracle based system. The Windows

version was called Logician and has a strong user group and shares

templates among users. It has been purchased by McKesson and folded into

their Centricity line of software. EPIC or EPICare is written in a

language similar to MUMPS and has a proprietary database. For small

practices it is very expensive. For very large practices, it can be

economical and has had its biggest success in massive networks like

Kaiser Permanente. It does have a windows interface and web versions. It

seems the common denominator for many existing systems and some new

systems is a web orientation.

“The Chart” is what providers ask for first. In the outpatient

setting, it has the lifetime history of the patient, unless you only

have the 5th of 5 volumes. If the file clerk doesn’t check and brings

you the 4th of 5 volumes, it doesn’t help much at all. In the inpatient

setting, there is no lifetime history. To the “modern hospital”, as in

the first hospitals, only the current episode of care has any meaning.

Because hospitals generate massive amounts of paper, it would be

impractical to present the user with a lifetime record. They couldn’t

likely carry it around anyway. As any paper folder has a tendency to

tear and degenerate, a trade off in quality of materials has too be

made. Expensive folders last longer, but cost more. The filing system

used has to be chosen carefully. Most small operations file by last

name. This creates a problem when people marry or otherwise change

names. It requires all of the diverse cultures to adopt the

Judeo-Christian format of names which can cause confusion. Most large

systems require patients to have a medical record number (MRN). Some

hospitals call it a “history number”. This frees the system from

reliance on names. Unfortunately it creates its own conundrums.

Duplicate MRNs can represent up to 20% of charts. Information filed

under a duplicate is unavailable to the treating provider. To prevent

the size of the medical records department from increasing and taking

over the whole care setting, some thinning must be done. Charts of

patients not seen in a certain time, usually 3-5 years are boxed and

removed to an archive location where square footage is not as expensive.

Unfortunately if the patient returns from a long absence and needs care,

there will be a delay in retrieving the previous information. As you can

imagine the archiving process offers multiple opportunities for losing

information. A careful record of which charts go where and when was the

last visit was must be kept. Among active records, tracking exactly

where a chart is constitutes a large part of a medical record

technician’s time. If a chart is pulled from the shelf for a phone call

and then returned to the file room, it must be retrieved for a scheduled

visit. If the scheduled visit is in urgent care the same day, it

requires an extraordinary system to get it to where the patient and

provider are meeting. Bar codes on each chart can help, but add a layer

of work and expense in keeping track of them. The physical folder

becomes a marker for itself. The only way to know if you have the

information is to hold it in your hand. Of course, the physical folder

can only be in one place at one time. Auditing a chart takes it out of

circulation. When a provider holds a chart as a reminder to follow-up on

a patient, that makes the chart unavailable for other caregivers. For

the very sick patient, in the hospital setting it is very common to have

3 or 4 individuals with an interest or need to have the chart at the

same time.

Realizing that paper charts were a poor basis for a sophisticated

information system, medical records professionals tried to improve them

by adding additional labels and flags. A physical patient folder is not

intrinsically identified until a physical label with either a name or

number is placed on it. A sticker is placed when a file is accessed for

the first time in a given year. This is used to indicate when the folder

should be archived. Allergy warnings are placed on the outside of the

folder, but may not be kept up to date or reviewed by all providers and

therefore are ineffective in their purpose. Sometimes birth dates are

put on folders. Some departments place insurance information on folders.

All of these are symptoms of an inadequate information system starting

with the paper folder. Within the paper record there is typically an

insurance form filled out with insurance account numbers, next of kin,

sponsor information and in many practices there is an initial history

form. All these forms contain information that changes. They contain a

mixture of administrative and clinical information. The chart is

typically the purview of clinical professionals and doesn’t routinely

get routed to administrative personnel to keep the information up to

date. The clinical information recorded at intake is a snapshot at best

and doesn’t fit into the usual workflow of the provider. One of the

quality markers looked for in audits of patient charts is a problem list

that is up to date. The paper problem list is either ignored or

inadequate. For simple problems providers don’t feel it necessary to put

everything on the list. For complex patients with multiple interacting

problems, there is no good way to represent the relationships between

the problems. As an additional disincentive, in a capitated environment

the complex patients are reimbursed at the same rate as simple patients

and therefore there is no time to do the additional paper work of

keeping the problem, medication and allergy lists up to date. Looking

for a progress note or lab result related to a problem list item is all

but impossible in most paper based systems.

Within paper records whether they are true source oriented, which is

rare today, or nominally “problem oriented”, there are dividers in the

chart which indicate where the documents come from. In essence all paper

charts have to be source oriented.

Progress notes, lab results, radiology results, consultant notes are

all kept in separate divided areas of the chart. Providers frequently

like to compare lab results over time. If lab results were filed with

the progress notes that generated them, that would not be possible. Also

lab results related to multiple problems are ordered and reported

together, so it is essentially impossible to have true problem oriented

paper records. In order for billing to be supported, each progress note

and consultation report must include much redundant information. This

generates massive amounts of text for documentation purposes only which

does not contribute to a provider’s understanding of the patient’s

problems. While searching for relevant information, this boilerplate

text just gets in the way.

Another bad habit made necessary by paper records is the recording of

clinical information on lab and x-ray result documents. Ideally every

provider would request the chart to be pulled from the record room to

document the results of every lab and x-ray. In this way the notes

relevant to the care of the patient could be appended to the progress

note that generated the test or x-ray order. When subsequent providers

or students review the chart, they can follow the notes that the

provider makes to guide their understanding of the provider’s thinking

process and teach students the “why” of what they did. This is in the

best tradition of Dr. Weed’s vision of medical records that guide and

teach. In the real world, providers look at a result and try to remember

the patient, make a note on the report itself about what is to be done,

or document that they discussed the finding with the patient all without

benefit of the rest of the chart. Pulling the chart each time would

double or triple the work that the already stretched medical records

departments do. If the provider elects to keep the chart until the

results come back, another inadequate situation develops. If the patient

delays getting the test done, the chart could sit for a long period of

time and be unavailable for patient care or audit or administrative

functions. The medical records personnel are judged on what percentage

of charts they can deliver and these sequestered records are not

available. Chart sweeps to open doctors’ offices and pick up piles of

charts are sometimes done which completely destroys the reminder

function of the paper record. Many providers have a “shadow record”

where they keep reminder information which must be duplicated to the

paper record at some point. There is no theoretical scenario in which

paper records could be made ideal even with massive personnel support.

Although electronic systems that are truly “paperless” are few, as

more of the patient record function is moved to networked computers, it

becomes more of a virtual record. Most practices that use electronic

records still print and file documents in a traditional paper chart to

satisfy legal requirements for pen and ink signatures. Legislation that

has legalized electronic signatures in some areas has helped move

electronic records forward. A virtual record does not have a physical

location. It is pure information. You can not point to a standalone

computer or even a network server as the location of the information. In

some systems part of the information is embedded in the client software

or browser and other parts in the server database. Replication of

databases and backups create equivalent copies in multiple places.

In a virtual record there is no limit to the number and kinds of

flags and labels that can be applied to a patient’s record. The physical

paper file no longer has to be the marker. Multiple volumes are not an

issue. You no longer have to decide on a single filing system. All

records are filed by a primary key which by definition has no relation

to anything specific about the patient. Charts are not filed by Social

Security Numbers, history numbers, MRN, birthdays, phone numbers or

names. Because of this ANY of the foregoing can be used to locate

records, which should be purpose of “filing” records. When you have a

virtual record the concept of an enterprise master patient index (EMPI)

starts to make sense. The EMPI keeps track of each specific system’s

identifying information for the entity known as the person. Creating

duplicate records for the same patient is much less likely when all the

details are brought to the attention of the registration clerk.

Instead of duplicating computer based demographic and insurance

information into paper forms in a paper chart, the virtual record simply

links to the actual information in a table. This is where the owner of

the information will be keeping it up to date. When all information

users reference a single information source, less mistakes and re-dos

are necessary resulting in a higher quality, more efficient service.

A problem oriented patient record starts to make sense if it is

electronic. You can use the problem list as an index of the medical

record. All references to a problem can be accessed by linking from the

problem list. The medication list is always up to date because that is

how medications are prescribed and refilled. The allergy checking

function becomes a prominent part of practice by fading to the

background, but becomes 100% effective.

Instead of depending on a few preset dividers to organize the

information in the chart, a provider can choose any number of ways or

“views” for his or her charts or for a particular chart. “Thinning” a

chart is when a medical records professional tries to imagine what a

provider no longer wants to see and takes it out of the the paper chart.

With a virtual record each provider can create any number of ad-hoc

thinned charts.

The progress note function can be divided into various purposes. At

some point, payers will realize Evaluation and Management (E&M) coding

is passé and adds no value to the interaction. Until then providers can

still instruct the EHR to create “progress notes” to satisfy whatever

coding level they believe is appropriate for a visit. If on the other

hand, the provider wants to view the data in a more efficient manner a

view can be constructed at any time since the data is coded and remains

unchanged in the underlying database.

Instead of always reading the transcribed reports of radiologists, if

the institution has an electronic image archive, the primary care or

other specialist can look at the actual image on the screen to explain

to the patient or double check for themselves.

One of the most powerful reasons to evolve to the electronic record

is security. The roof leak or flood scenario could put a paper-based

organization out of business. Paper records can be physically stolen and

there is no backup available. Paper records can be photocopied and there

is no way to detect the act. Anyone with access to the file room

technically has access to stealing, altering or copying any record from

the shelves. Electronic records can never be stolen or damaged if

backups are properly done. Everyone who accesses a record for whatever

reason can be audited for review by a appropriate security official or

by the patient themselves in some systems. No copies or alterations are

possible without leaving an audit trail. We can give certain people full

access to a particular record for audit or other reasons and they do not

inherit access to any other record. Currently it is against any medical

records organization rules to physically take records out of the

building. There are many good reasons to have this rule. It is routinely

broken in some organizations by well-meaning providers who can’t get all

the work done during the day and need to finish documenting at home.

With an electronic system, it is unnecessary. A particular chart can be

securely viewed anywhere in the world with proper security precautions

that have already been established and tested in the banking world. In

the same vein a chart can go with the patient to the cardiologist and be

back for the primary care visit even if the appointments are minutes

apart because the chart never actually goes anywhere. Paradoxically, the

chart can go more places because it doesn’t actually go anyplace!

One of the markers of a high quality product is reduced variability

in the final product or service. With paper records it is so inefficient

to tell exactly what kind of care is going on that only with a huge

budget is serious quality control possible. By careful design of

templates and data dictionary and automatic 100% auditing of important

aspects of care, the virtual record makes consistency and high quality

attainable goals.

Reminders in a paper system are of two kinds. The chart surrogate is

the most common. Keeping the chart as a marker for a sick patient or an

important result does work, but the chart is unavailable for other

unrelated care in other locations. The other reminder occurs when

providers create a “shadow chart” by keeping a separate note book of

patient names, medical record numbers, multiple contact numbers, an

abbreviated problem list and the actual reminder. Then they can manually

review the list at intervals to see whose results has not come back.

Even so, chart pulls are required to check on details and document

results taken over the phone. The frequent, tragic and needless failure

to diagnose cancer and other serious illness because of failure of the

reminder function should embolden providers to try anything else because

of the manifest failure of paper systems or at least the tremendous

additional labor involved if they are properly done.

From time to time in looking at paper charts providers will come

across an article photocopied and stapled or bound into the record. This

may have been from the patient or a student and would likely have some

tangential relevance to their conditions. Instead of being the

exception, an intelligent virtual record could have routine protocols,

care paths, guidelines and evidence based advice just a click away.

Link-outs are possible in a virtual record connected to the Internet.

Even if the record is stored on a single computer and inaccessible from

the internet, a link to a library of full-text references could add

measurably to the care of the patient.

Reminders, embedded Intelligence and Link-outs are a feature of

Electronic Health Records called Clinical Decision Support which is not

available in paper records. Features such as evidence based order sets,

evidence based templates for progress notes are another form of clinical

decision support not as easily provided in the paper record.

The busy provider rarely has time to notice the random photocopied

article in the occasional chart. To enhance a patient oriented

education, they could jot down the reference and look up and study the

article. But the reference could be tangential or exceptional and not

helpful for most other patients. What if the provider could leave a

bookmark in the chart of a patient - not visible to other providers or

auditors or to the patient, but kept in a special place that the

provider could reference from home or elsewhere during a continuing

education activity? What if providers could actually list their

information needs without making that knowledge known to anyone else?

What if they could audit themselves and design an education program

specifically for their weaknesses and in the light of their learning

style and strengths in other areas? Or better yet what if their

information needs were anonymously feed to specialist in the appropriate

area to have a suggested program designed for them and feed back

anonymously? Why not give them CME credit for actually looking up and

learning information in the course of their daily practice? The current

answer to these questions is that it is impractical or impossible. With

a virtual record it becomes possibly to seamlessly transition from

patient care to professional education.

Many electronic systems currently have extensive patient education

modules. It is a small step to create mass customization for each

patient’s problem list.

Extending the ability for patents to read and contribute to their

record is available in many EHR systems. When patients are finally

incorporated into their care the concept of problem orientation will be

the only reasonable way for them to look at the chart. Patients are

expert at what bothers them, but clueless about ICD9 and CPT codes that

payers require.

The ability of a system to be organized truly in a problem oriented

way will separate the pack of contending vendors. The data will be

stored in a fully coded technically correct manner, but the various

views will be enabled depending on the needs of the user.

It is very expensive to audit paper records. If you can’t read a

contributor’s handwriting it is impossible to audit the care they are

giving, appropriateness of their reimbursement coding or in some cases

even know who they are! Electronic records can audit themselves. Audit

could become enmeshed in the continuing education that a provider

designs for themselves. Some of the reasons for auditing will disappear.

Use of appropriate E&M templates will ensure that appropriate codes are

being submitted as a matter of course. In the future, as the more

complicated systems come into use, the knowledge of coding will become

so arcane that no human could do it in real-time anyway. No “education”

will be needed because the need for the skill will go away!

Demand management is the managing of demand for health care. As any

provider will tell you, if you don’t have the diagnosis after taking a

careful history only a few strikingly unexpected physical exam findings

will help. The physical exam only confirms your suspicions in most

cases. If history taking could be automated and monitored over the web

in real-time by nurses backed up by physicians, the demand for actual

face-to-face appointments would decrease. Much of health care could be

accomplished over the web with brief confirmatory visits in some cases.

When actual visits or phone conversations are deemed necessary,

access management comes into play. Locating resources to match patients’

needs is best done by cell phones augmented by portable networked

information appliances. In the current model physicians are called and

have to be brought up to date or up to the minute on a patient’s status.

If the physician had a summary of the patient’s status they can

contribute immediately or preemptively to the care of the patient and

avoid the need for an actual phone conversation and the “bringing up to

date” function. Virtual records like EHRs can take health care to the

next level of value for patients and providers.

The thrust of electronic commerce or e-commerce is to become

intertwined in the daily routine of users. Whether it is banking

services expanding into full financial services or bookstores selling

items with no relation to books, e-commerce seeks to enmesh itself, add

value and become transparent to the user.

E-commerce has to first create the need for itself. It must do

something so much better than the bricks and mortar alternative that

people chose to migrate their activities to the virtual sector and

abandon their old ways. In all sectors this is difficult. In the health

sector we have a few things pushing us to the electronic realm. Bricks

and mortar and face-to-face are expensive compared with web access

anytime and anyplace. If we design systems that look and feel like the

providers workspace and create value for patients to exploit, the public

will assign electronic healthcare “need” status. It may be by

financially competing so intensely with bricks and mortar that a

face-to-face encounter will become an extraordinary and expensive event.

People have shown they must have value to change established patterns.

An inferior service at a lower cost will not likely prevail, especially

in a robust economy where people can well afford the current cost of

face-to-face care. A service that cost the same or less out of pocket,

but is easier to use, quicker to get to, automatically follows up on

treatment plans, educates you and connects you more closely to your

provider will drive traditional healthcare services out of the market.

It is likely that a bricks and clicks strategy or a symbiosis of

existing physical entities will prevail. In that model, most of the care

could occur virtually using EHRs. When a physical visit is needed, the

established physical entities like clinics and hospitals will be needed.

If a large percentage of care occurs without a visit or phone call by

interactive history taking guided by a mid-level provider or nurse, a

practice can take more capitated lives. They will still need to see

patients but they become more efficient by avoiding unnecessary visits.

When patients use the service as a matter of course, provider

organizations can extend into health related areas. Discounted exercise

equipment linked to the web for feedback into your personal exercise

program, grocery buying with reminders for healthy foods and feedback

about total calories, disease specific extensions of care beyond

traditional medical care into life enhancements chosen by the provider

are all made possible by a virtual practice. Providers still have the

ethical responsibility to put their patients’ welfare above profit.

Endorsements and web-site links have to be chosen with this in mind, as

always. It may be controversial, but this evolution can be done in a way

to preserve the best of the healer-patient relationship. Ultimately it

will start when we give ourselves permission to re-define healthcare in

a broader way and it will thrive when we immerse our patients in mass

customized health promotion messages.

Any EHR must be built on a repository of clinical data. Some have

designed the repository into the EHR itself. EpicCare is an example of

that kind. Other EHRs keep some of the data themselves, such as the

clinical notes the system generates itself, but links to a repository of

lab and other results. A Clinical Data Repository (CDR) is characterized

by having patient identified real-time clinical operations data in a

normalized form that is coded with a data dictionary. It is optimized

for individual patient centered queries and not research queries across

multiple patients, although theoretically those queries could be run.

The CDR is the source of results for providers seeing patients. The lab

and imaging results go directly into the CDR for immediate availability

for in and out patient care. The portion of the CDR for clinical images

is called a Picture Archiving and Communicating System or PACS.

Interfaces are built, usually using the HL-7 or ASTM standards to

existing legacy and reference lab systems. Different codes from feeder

systems are standardized into a common lexicon so that results can be

compared between systems if a patient’s insurance (and therefore

reference labs) changes. Some pure CDRs have gone into the EHR market by

improving their user interface and adding EHR-like functionality and

decision support tools. Ultimately it may be hard to decide between the

two kinds of systems. In a large enterprise a better choice will usually

be a CDR due to the need for robust large scale data manipulation. In a

small enterprise a pure EHR will frequently be the best choice for

economic reasons. The CDR can contain outcome measures and is the

enabling technology for population based care and research. In a pinch,

limited research queries can be run during idle time in the evening and

weekends on a pure CDR database without creating a research data

warehouse.

Practice partner and Logician are two products that have paralleled

each other’s development with Practice partner targeting small to mid

sized practices and Logician targeting mid to large organizations. Now

that both have developed web based products or delivery mechanisms, they

compete in the same niche. Patient profile is an system created by an

attending physician and a resident programmer in Microsoft access for

local use in a clinic. It is shown to demonstrate some generic qualities

of EHRs.

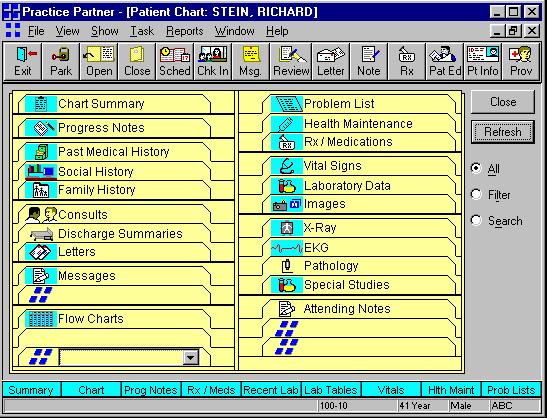

Figure 1: Example of Use of Tabs in Practice

Partner

The tab metaphor is a very powerful one for designers of EHRs. The

security of a paper metaphor is too strong to be resisted, so many EHRs

that have progressed passed the cascading menus of DOS programs use this

appearance. With most programs, there is more than one way to accomplish

a task. IN Practice Partner (Figure 1) ,the large buttons on top expose

the same functionality as the tabs in the foreground. The chart summary

is top left followed by progress notes since they have the summary of

most recent events. The main past history which changes only slowly is

Past/Social/Family history. The next section is consults, discharge

summaries and letters followed by messages and flowcharts. The problem

list occupies the predominant position on the right side of the screen.

The health maintenance area is conveniently located below problems and

above the Rx pad. For detailed data the vital signs, lab data and images

are next followed by x-ray, ekg, pathology and special studies. The

design is very flexible and most tabs can be rearranged or omitted.

Logician Internet uses the typical web page format with hierarchical

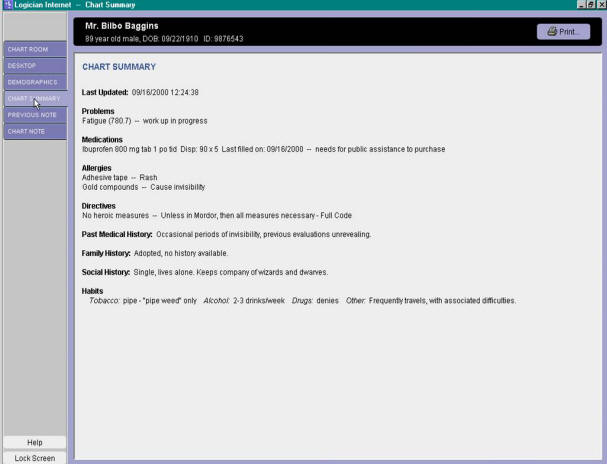

information on the left and details in the right frame (see Figure 2).

Information starts from most general at the top left:

- Chart Room

- Desktop

- Demographics

- Chart Summary

- Previous Notes

- Chart Notes

The Logician Internet web technology is improved by being implemented

in Java on the local machine to avoid variable network delays in screen

refreshes and enables a complex and detailed program. This creates the

need to synchronize the local database with the reference database and

also between different users of the chart.

Figure 2: Display of Information in Logician

Electronic Health Record

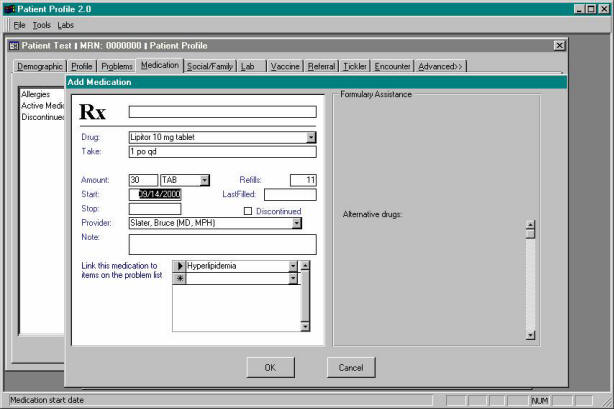

Profile has functionality for prescription writing which goes beyond

it’s CDR function (See Figure 3). In this screen you can see behind the

pop-up to see lists of Allergies, Active Medication and Discontinued

Medications all together for easy reference. In the background are the

other typical tabs of the EHR chart sections. The pop-up gives the

impression of a written Rx which is called an affordance. That is it

affords the opportunity to enter prescription information. The central

drop down has a list of all medication available. The list is available

on the web and can be updated on a weekly basis. Below the drop down is

the free text Sig: area followed by the amount dispensed, the type of

preparation and number of refills, the start date, the prescribing

doctor, some free text notes and a link to a problem from the problem

list. On the right you notice the formulary area which would indicate

the formulary status and alternate suggested drugs. By having a list of

medications a provider can check off which ones to refill and make a

repetitive task easier.

Figure 3: Functionality for Prescription Writing

in Profile Electronic Health Record

The Regional Health Information Organizations are

organized to facilitate exchange of information among health care

providers. George Mason University is proposing to organize one

such organization to serve providers of care in wider Washington DC

metropolitan area. The goal will be to allow designated providers

access to the patient’s complete record independent of where the patient

has received services. The organization will enable large and small

health care providers to effectively communicate to each other about the

care of their common patient.

A test ordered by the primary care physician will be

readily available to the specialist and vice versa.

In addition to improving patient safety and

quality of care, the integrated data is expected to reduce overall cost

of care, enhance health services research, enable detection of public

health outbreaks, and improve patient’s access to health information.

Principles of Operation

The Regional Health Information Organization (RHIO)

will be based on the following operation principles:

1.

Voluntary. Health care organizations voluntarily

choose to participate in RHIO.

2.

Public notification. Participating health care

providers will prominently display a sign informing their patients of

the organization’s participation in RHIO.

3.

No centralized database. No data is maintained by

RHIO. The organization maintains communication protocols and maps of

data structures, which will enable transfer of data from one

participating organization to another. RHIO does not require a uniform

data structure among all participating organizations.

4.

On demand transfer of data. At point of care and on

demand, RHIO will enable a provider of care who has client’s permission

to gain access to all data on the client in participating

organizations. Each participating organization will process the request

for transfer of the data on demand.

5.

Algorithm based record identifier. RHIO will not use

any unique identifier for matching the patient’s records across several

providers. Instead, clients will be matched based on automated

algorithms. Details of the procedure are provided

elsewhere.

6.

HIPAA compliant. George Mason University’s

Institutional Review Board will supervise the data safety issues related

to the proposed organization. No data will be transferred without

authentication of the provider and verification that the patient has

signed a consent form. Participating organizations will maintain the

signed consent forms of the patients.

7.

Data mining & research Health care researchers will be

allowed to have access to the data after removing patient, provider and

organization’s unique identifiers.

8.

Personal records. Patients will be allowed to review

their records and suggest changes to participating organization.

9.

Online health education. Patients will have access to

confidential health information tailored to their needs.

10.

Public health monitoring. RHIO will allow public

health agencies to use the data to monitor outbreak of diseases.

11.

CMS review organizations. RHIO will work with Center

for Medicare and Medicaid Services peer-review organizations to provide

assistance in analysis of improvement trends.

12.

Free EMR to small and safety net clinics. RHIO will

provide the Veteran Administration’s Vista Electronic Medical Record

free of charge to all participating clinical groups of less than 12

clinicians. In addition, RHIO will provide free training and

maintenance services for these clinics if the State supports the

University in accomplishing these goals.

It seems odd to think of all the changes in the rest of our lives

brought about by the internet and then to go and sit in the waiting room

of a doctors office and read old People magazines and fill out paper

forms. Ultimately healthcare will be as different as airline

reservations and banking have become, or more. We are seeing, in some

places, truly modern information enhanced practices with EHRs spring up

and thrive. The ruts of the past are deep, but the need for advanced

practices is too strong to resist. Existing practices are gradually

enhancing their appeal by adding virtual elements. So the first

competition will be avant-guard providers reaching out over the web and

taking patients away from plain waiting rooms. Patients who see value in

this and respond by putting up with the inevitable bumps in the road

will be able to shape the future of healthcare.

Lærum H, Ellingsen G, Faxvaag A.

Doctors' use of

electronic medical records systems in hospitals: cross sectional survey.

BMJ 2001;323:1344-1348 ( 8 December )

Mitchell E, Sullivan F.

A descriptive

feast but an evaluative famine: systematic review of published articles

on primary care computing during 1980-97 BMJ, Feb 2001; 322:

279 - 282.

Majeed A, Lusignan SD, Teasdale S.

Ten ways to

improve information technology in the NHS • Commentary: improve the

quality of the consultation • Commentary: Clinical focus might make it

work BMJ, Jan 2003; 326: 202 - 206.

Mandl KD, Szolovits P, Kohane IS, Markwell D, MacDonald R.

Public standards

and patients' control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible

but private • Commentary: Open approaches to electronic patient records

• Commentary: A patient's viewpoint BMJ, Feb 2001; 322: 283 - 287.

The following additional resources are available to help you think

through this lecture:

u

Prepare to present one of the articles in the reading set.

|