Objectives

-

To review the literature on patients' reactions to

computers

-

To describe nature of online patient education systems

-

To understand online health

education is effective

This document is based on in part and at times verbatim on an article in the

Supplement to Medical Care authored by Farrokh Alemi and Richard Stephens and titled

"Computer services for patients: Description of systems and summary of

findings." In addition, it is also based on a chapter by Alemi F and Stephen R titled

"Electronic communities of patients: computer services through telephones" and

published in Brennan P, Schneider S. (Editors) Community Health Information Networks,

Springer, 1997.

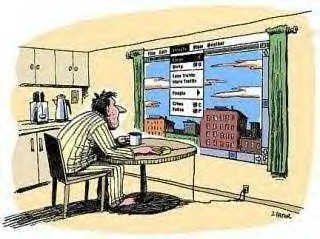

A quiet revolution is underway about how care is being delivered to

patients in the United States. Information Technology is radically changing the nature of

clinical practice. In the following sections we review examples of how this is being

done and speculate about the implication of these changes for organization of health care. In discussing the impact of IT on clinical practice, we focus

primarily, though not exclusive, on online services. This is one of the newer areas

of growth of IT and provides some of the most striking ways in which IT affects health

care.

Like all technological innovations, early implementations of

technology do not raise later implications. No one in the early days of black and white

television could have imagined that this technology could lead to increased violence in

our society or affect presidential elections. But new media often goes beyond what it was

planned for. Slowly but surely changes are underway that will radically alter

how Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO) are organized and how providers deliver

services. The remainder of this section reviews existing research on impact of information

technology on practice of care and lays out one scenario of how the near future would be

like. This section helps you think through these technologies and understand how it will

affect providers and health organizations.

Providers and patients can use computers to do many activities. Among these are:

health education, social support, appointment making, taking history, and home

monitoring.

Several HMOs are using computer services to patients' homes for

educating their members. There is overwhelming data that health education (predominantly

through books) is effective in reducing cost of care and improving quality of services.

Data suggest that consumers who know more about their health engage in more active self

-care, are more likely to comply with their treatment, are more effective participants in

choosing treatment options, and have lower health care costs., One approach to providing

health education at home is through telephone access to a nurse. Patients call a nurse

who, usually based on a computer protocol, advises callers to seek the appropriate level

of care.- Another approach uses a librarian who helps patients shape

an inquiry and then searches computerized files for the requested information. The

librarian either provides the information to the patient over the telephone or mails the

information to the client. In a third approach to health education, patients can telephone

a computer; press touch-tone telephone keys corresponding to a particular taped health

message, and listen to it. In a fourth approach, investigators have tried to educate

patients by providing them with a computer and allowing them to interact through the

computer with health professionals. Patients type their questions and the computer sends

these questions to the computer of a health provider, who types in a response at a later

time., Finally, in a fifth approach patients call a computer and record their

questions, the computer calls the provider, who records his/her response, and then the

computer calls the patient back to deliver the answer.

Some HMOs are using computers to help patients who have similar illness

to talk and exchange opinions with each other. No matter how well informed patients are

about their medical condition, most need the reassurance of talking to others who have

been in similar situations, who can demystify the health delivery system, and who can

provide emotional and social support when things are not going well. Lack of social

support, obviously, increases loneliness and puts one at risk for depression and mental

illness. Lack of social support also affects physical illness and drug use. Studies

demonstrate that face-to-face group support is important to a patient's recovery, but

experiences of self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous

meetings show that clients miss many group meetings. Chronic illness restricts

participation in social activities. When patients lose their own community of friends, or

find that their existing friends cannot satisfy their illness related information needs,

patients may attempt to organize or participate in new communities and self help groups.

Naturally, they seek to organize these communities around their illness. Distance from

each other, lack of time, chaotic and busy life styles, and confidentiality limit

patients' participation in support groups. To facilitate the creation of intentional

communities of patients, some have suggested the use of electronic bulletin boards., Through these bulletin boards patients at long distances from each other

can communicate in an asynchronous and confidential manner. With the spread of Internet

and commercial on-line services there are increasing numbers of electronic bulletin

boards. Investigators at the Maryland School of Nursing have provided electronic bulletin

boards to disabled persons. Others have used the computer to assist in promotion of

controlled drinking among early stage problem drinkers.,, In

Washington, CapAccess provides a platform of bulletin boards and computer services for a

diverse patient population. In Miami, elderly use computer bulletin boards to break their

isolation and have mental simulation. In Cleveland, caregivers of persons with dementia

are using computer bulletin boards. In northern California, a major HMO is using

voice-bulletin boards to allow recovering alcoholics to have access to each other.

Some HMOs, e.g. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Northern California, are

working on ways of allowing patients to make appointments using their computers. The main

advantage of computer based appointment making is the possibility that the patient can set

and learn through the computer about the urgency of the visit and the self care steps that

they can initiate. In one scheme (not yet implemented), patients make an appointment, then

answer questions about their symptoms. The computer analyzes these responses and sends

them to a clinician; who based on his/her first hand knowledge of the patient, will record

a response to the patient. The response may include a recommendation to (1) by pass the

provider and seek advice from a specialist, (2) seek immediate care, (3) seek care after

completion of laboratory tests, (4) wait and see how the illness progresses. These types

of triage decision making are the core advantage of how computer assisted appointment

making may radically reduce the number of intermediary office visits and lead the patient

to the appropriate and final level of care.

Computers can be used to assess the patients before their office visits

in order to alert the clinician about some underlying problems. Office visits provide a

limited time for patient and clinician interaction. Computers can assist by gathering the

necessary information ahead of time and alerting the physician to key findings in the

patients' condition. In one study, patients were asked to call a computer and participate

in risk assessment. The computer analyzed their responses, established whether they were

suspect alcoholics, and sent the analysis to the patients' clinician. When patients came

for visit, the clinicians reviewed the findings with them.

Computers can be used to monitor patients' health at set time

intervals. For example, Visiting Nurse Association of Cleveland has designed a computer

system that calls their patients with congestive heart failure and asks them a series of

questions on a weekly interval to assess the need for out of plan visits to patients'

homes. Patients answer the questions by pressing keys on their telephone pad or by

recording their answers on the computer. If answers are recorded, the computer sends the

recording to clinicians, who listen to and respond to the patients' responses.

Patients' reactions to computers are not simple. Patients may like

some computer services more than other services. For the most part, on-line services seem

to patients more like communication devices than data collection and calculation

computers. Most of the systems involve a short interaction with a computer followed by a

free-form interaction with other people through the computer. Data show that most patients

welcome these communication aids. When hard to reach individuals were asked to rate

computer calling them, versus an answering machine or a computer sales call, they rated

computer services positively and similar to an answering machine; while they almost

uniformly expressed a negative attitude towards computer sales calls. If computers help

communication, patients will like them and will not think of them as they have

traditionally thought of computers.

Some of the on-line activities (e.g. the systems designed to take

medical history and to triage the patient) do involve extensive data collection and may

irritate patients. While computers are expected to improve the interview process through

standardization, it is possible that computerized assessment will anger and frustrate

clients who have turned to the health care system in part because they needed human care

and attention.

Data indicate that contrary to expectations, patients prefer

computerized telephone assessments and CRT-based computer assessments to assessments

conducted by an interviewer. This is especially true when patients must report on

confidential matters (such as drug use, sexual preferences, suicidal thoughts, etc.). Such

preferences have been known since the late 1960's and have been demonstrated in far too

many studies to be considered just an artifact. One explanation for such preferences is

that computer interviews are non-judgmental, while clinicians, by their very own status,

may be perceived as judgmental. Another explanation is that patients prefer the self-paced

self-administered nature of computer interviews. Still another explanation is that

patients prefer a non-verbal interaction because it helps them be more introspective.

Whatever the reason, it is clear that patients like computer interviews.

Our own experience is also telling. We created a system for

automatically interviewing patients about their health risks, advising them about what

lifestyle they should change, and referring them elsewhere. We compared reactions to this

system to receiving health information from magazines, television or a health

professional. Data were collected from 96 randomly chosen employees of Cleveland State

University. Employees were invited to participate based on a stratified sample that

encouraged enrollment of males and females and enrollment of faculty, professional and

non-professional staff. When the subjects received a post card and a follow-up letter

announcing the availability of the system and a phone number where they could call and use

the computerized health risk assessment, the majority (71%) of subjects used it. When they

called a computer interviewed them and based on their risks gave them advice for modifying

their life styles. Those who did not call gave various reasons (some did not use the

system because they could not read the material mailed to them). Less than 4% did not

participate because they objected to a computer giving advice on health risks. Those who

used the system rated it as more accurate, easier to understand, more convenient, more

affordable, easier to use, and more accessible than health education received from

television, magazines, or health professionals.

These data clearly show that subjects are open to and like computer

interviews about their health risks, do not mind receiving advice from a computer, and

prefer this method of screening to existing source of health education. These experiences

further confirm the literature finding that patients, once familiarized with the

technology, accept and enjoy it.

In our experience, the most negative reactions to computers advising

patients and triaging them to care comes from those who represent patients (some

clinicians, newspaper journalists, and lawyers). An example can demonstrate this. At the

onset of our research, the local newspaper, Plain Dealer reported our funding in its first

page and one of its editors wrote a very negative opinion. The editor ridiculed the use of

computers for management of patients, in this case for drug-using pregnant patients.

Shortly after the media attention, drug treatment groups organized a widespread boycott of

our work and refused to allow their patients to participate. Eventually the boycott broke

and we were able to recruit patients and conduct our work. Contrary to the editor's claim

the data showed that patients liked our services; used our services; and these services

improved their care. The self-appointed advocates of patients took a position different

from the wishes and the best benefits for these patients. So, do patients resist computer

interviews? No and certainly not as much as their advocates do.

Satisfaction with a computer system depends on how the system is

organized. Most individuals are familiar with computer calls through telephone marketing

calls. Since these marketing calls are frustrating, most people believe that if a computer

calls, they will hang up on it. Consider the circumstances under which people hang up on

computers. These calls often arrive at unwanted times, interrupting other activities, and

furthermore, they are about topics of little interest to the receiver. Thus, it is not

surprising that people hang up on these calls. Suppose it was not a computer calling but a

sales representative at your door. When a salesperson shows up at your door, in the middle

of your dinner, and tries to sell you something that you do not need; obviously, you tell

him to go away. Now, consider if he were to come back every other day. Naturally, you

would be frustrated. The point is that your frustration is not with the door-to-door

salesperson's existence, but with what he is selling and with his lack of judgment and

timing. The same applies to computerized telephone calls. Computers, who call when the

patient has asked, deliver messages that the patient cares for, and do so in a reliable

fashion, are not frustrating.

Perhaps the most telling story of patients' reactions to computers

is what happened when we tried to stop on-line services that were monitoring patients on a

weekly basis. Our funding had run out and after five months of weekly computer calls, we

announced that we were planning to stop. The reaction was swift and overwhelmingly

negative. These patients did not mind that a computer called them and interacted with

them, but were angry when it did not. One patient put it this way: "For months you

have been calling and mothering us. How dare you stop?" It seems that patients who

become accustomed to on-line services may be frustrated if the service is withdrawn.

Computer services to patients may seem like a value-added service right now, but when it

is widely in use, it may become entitlement.

In the end, the most obvious test of whether patients' are satisfied

with computer services is their use of these services. Data suggests that many patients

are using these services, making it the question of whether they like computer services

rather irrational. Why would patients use a service that they do not like? We will review

some of these data later when we examine the potential impact of on-line services on

patient outcomes.

Caregivers to

Alzheimer's patients improve their abilities

Investigators gave computers to caregivers of

Alzheimer's patients and provided them with on-line services. Patients were randomly

assigned to the control and the experimental groups. After providing them with support

through computer bulletin boards, both the experimental and the control caregivers still

felt isolated. Access to the computer did not change their sense of isolation. However,

significant differences were observed in clients' coping skills. In particular, patients

who had access to computers were more confident about their own abilities to cope with the

burden of giving care.

For more on this topic select one of the following options. When

you do so, the computer will conduct a pre-set search of Medline database and provide the

results indicated.

-

For an abstract of the study or to order the study click here.

-

For another related report of the study click here.

-

Related articles

Based on Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW,

Bricker E, Pingree S, Chan CL. The use and impact of a computer-based support system for

people living with AIDS and HIV infection. Proc Annual Symposium Computer Applications Med

Care, 1994: 604-608

The clearest evidence that on-line services could help reduce cost

of care comes from a recent study on HIV/AIDS patients. Investigators provided 200 HIV

patients with a host of computer services, including a computer bulletin board for

support, email, question and expert answers, library of information, and decision aids.

Patients were randomly assigned to control and experimental groups. Only the experimental

group had access to the computer services. Among the various computer services provided to

the experimental patients, computer mediated social support was the most frequently used

service. Investigators evaluated the project after 3 months and 6 months. Surprisingly,

they found that access to the computer led to higher quality of life in several dimensions

including social support and cognitive functioning. The experimental patients also had

fewer office visit (dentists, primary provider and alternative care providers) and shorter

time per visit to the primary care provider, HIV and mental health providers. The

experimental patients were also less likely to be admitted to a hospital and more likely

to have a short stay. In summary, there was 33% reduction in total cost of care. These

data confirmed the importance of social support in bringing about behavior change and

showed that use of electronic groups as well as other computer services could lead to

drastic reduction in cost of care.

For more information, click on the items below and a

Medline search will be conducted for you.

-

See the abstract of the study.

-

See related work.

Based

on Alemi F; Stephens RC; Javalghi RG; Dyches H; Butts J; Ghadiri A. A randomized trial of

a telecommunications network for pregnant women who use cocaine. Medical Care, 34(10

Supplement): OS10-20 1996

A study examined the impact of electronic communication (use

for provider contact, for on-line testimonials and religious services) and electronic home

health education, on care of 179 drug using pregnant patients. Patients were randomly

assigned to control and experimental groups, only the experimental group had access to the

on-line services. Patients were interviewed at enrollment (usually during the third

trimester), at delivery and at 6 months post delivery. The electronic communication

portion of the system was used on the average 2.3 times per week per patient. The home

health education portion was used 0.2 times per week per patient to leave a question and

1.9 times per week per patient to listen to questions. These data showed that poor, drug

using, pregnant, under educated, and multiple resident clients could use on-line services.

Most patients used the service to communicate with clinicians and their friends, and not

to learn more about their condition. However, a sizable minority (45%) of the patients

used the health education component at least once. Unfortunately, despite this use there

was no difference between the experimental and control group in outcomes of care. Mere

access to, or occasional use of, the system did not lead to any significant difference in

outcomes of care. On-line services had a benefit, when patients used the systems more

extensively. Patients, who used the system more than 3 times a week (about 1/3 of the

experimental group), were 1.5 times more likely to be in treatment than patients who used

the system less frequently; this finding persisted, even when controlling for differences

among patients at baseline.

There seems to be a threshold after which the use of on-line

communication systems has a positive impact on treatment compliance. Despite the success

in bringing some of the experimental patients to drug treatment, participation in formal

drug treatment was not effective in reducing the drug or the alcohol use of this

population.

Click on the following for a search of Medline for related articles or the abstract of

the study.

-

For

the abstract of the study or to order the study click here.

-

For related studies click here.

Based on Alemi F, Stephens RC, Mosavel M, Ghadiri A, Krishnaswamy J,

Thakkar H. Electronic self help and support groups: A voice bulletin board. Medical Care

1996, 34(10 Supplement): OS32-44.

One study examined the use of electronic support groups. The study

was conducted on 53 recovering drug users. Half were assigned to electronic and half to

face to face support groups. On the average, patients used the bulletin board 2.18 times

per week and 96% of the patients used the voice bulletin board. Patients were more likely

to participate in the voice bulletin board than in the face-to-face meeting.

The mean number of biweekly participants in the voice bulletin board

was 8.09 times higher than the face-to-face group. The majority of the comments left in

the bulletin board (54.6%) were for emotional support of each other. There was as much

expression of emotional support in the early parts of the meetings as in the later parts.

No "flaming" or overt disagreements occurred. The more clients participated in

the voice bulletin board the more they felt a sense of solidarity with each other.

Members of the experimental group used significantly less health

services than members of the control group; and lower utilization of services did not lead

to poor health status or more drug use. These data suggested that voice bulletin

boards might be an effective method of providing support and that electronic supports

groups reduce use of health services without any apparent impact on health status of

patients.

The following options conduct a pre-set Medline search that may take

30 seconds to complete.

-

To order the paper or to read the abstract of the paper click here.

-

To read related articles click here.

Based on Friedman RH, Kazis LE, Jette A, Smith MB,

Stollerman J, Torgerson J, Carey K. A telecommunications system for monitoring and

counseling patients with hypertension. American journal of Hypertension 1996, 9 (4):

285-292.

This study examined the impact of computerized home monitoring and

counseling on elderly patients with hypertension. Investigators randomly assigned 267

subjects to control and experimental groups. The control group received their usual care.

For six months and on a weekly basis, patients in the experimental group called a computer

and reported to it their self-measured blood pressure. During these telephone calls the

computer interacted with the subjects to increase their knowledge of the disease and side

effects of the medication. In addition, the computer reported subjects' adherence to

medication use to their clinicians. The experimental group members were 6% more likely to

adhere to their prescribed medication than the control group. There was no difference in

systolic blood pressure. However, the experimental group reduced their diastolic blood

pressure by 5.2 compared to 0.8 mm Hg for the control group.

The following options conduct a pre-set Medline search that may take 30 seconds to

complete.

-

To

order the paper or to read the abstract of the paper click here.

-

To

read related articles click here.

Based on Alemi F, Alemagno SA, Goldhagen J, Ash L, Finkelstein B, Lavin

A, Butts J, Ghadiri A. Computer reminders improve on-time immunization

rates. Med Care 1996 Oct;34(10 Supplement):OS45-OS51 .

This study examined the impact of computer

reminders on on-time immunization rates. The experimental group received computer

reminders to keep their appointments and the control group did not. The patients included

infants, who were less than 6 month of age, were being seen at the outpatient clinic for a

first visit, and were patients of three attending physicians and three nurse

practitioners. These infants were compared to 77 infants from the same clinic, less than 6

months of age, and seen for the first visit during the same period by the same providers.

The patients who received computer reminders were more likely to show for their

appointments. The on-time immunization rate for experimental subjects was 1.19 times

higher than the control group. These data suggested that computerized reminders of the

patients led to an increase in the show rate at the clinic and an increase in on-time

immunization.

The following options conduct a pre-set Medline search that may take 30 seconds to

complete.

-

To order the paper or to read the abstract of the paper click here.

-

To read related articles click here.

Based on Wasson J, Gaudette C, Whaley F, Sauvigne A,

Baribeau P, Welch HG. Telephone care as a substitute for routine clinic

follow-up. JAMA 1992 Apr 1;267(13):1788-1793.

In a randomized clinical trial 497 men were assigned to usual care or

three scheduled telephone follow-ups. During the 2-year follow-up period, telephone-care

patients had 19% fewer total clinic visits, scheduled and unscheduled, than usual-care

patients. In addition, telephone-care patients had 14% less medication use, 28% fewer

total hospital days. Estimated total expenditures for telephone care were 28% less per

patient for the 2 years. Improvements in physical functioning was observed among

patients with poor health at start of study.

The following options conduct a pre-set Medline search that may take

30 seconds to complete.

-

To order the paper or to read the abstract of the paper click here.

-

To

read related articles click here.

Patients with access to interactive video disc on benign prostatic

hyperplasia had 11%-39% lower surgery rates than patients without access.

Click

here to search the Medline for more on this topic.

Men who viewed the educational videotape were better informed

about Prostate Specific Antigen screening test, prostate cancer and its

treatment; preferred no active treatment if cancer were found; and preferred not

to be screened. They were 9.9% less likely to have a PSA test by next visit.

This tendency for less PSA was not repeated in a second study.

Click

here to search

for more on this topic.

Providers who participated in a personalized decision aid were

26% more likely participate in hepatitis B vaccination than the group which

received only information.

Click

here to search

for more.

The following additional resources are available to help you think

through this lecture:

The growing number of studies on impact of electronic patient education and

social support on patients changes the question from whether these interventions

are effective to under what conditions they are effective. For a detailed

discussion see

enclosed review.

Advanced learners like you, often need different ways of understanding a topic. Reading

is just one way of understanding. Another way is through writing. When you write you not

only recall what you have written but also may need to make inferences about what you have

read. The following questions are designed to get you to think more about the concepts taught in

this session.

Please read the following 7 articles and prepare 1 of the following articles to discuss in class.

One of the best ways to master

a topic is to teach it. By presenting one of these articles, you get to

have in-depth understanding of the topic. For the article you plan to present, prepare a

slide show.

Bring the slides show to the class. Your presentation will be judged successful to the extent that you can

solicit your colleagues comments and input.

The articles for presentations are the following (remember to Logoff before

selecting to see another article otherwise the system will assume you are online

and prevent you from signing in again for 15 minutes):

- Gollust, Sarah E. BA 1,2,. Wilfond, Benjamin S. MD 1,2,. Hull, Sara Chandros

PhD 1,2.

Direct-to-consumer sales of genetic services on the Internet. Genetics in

Medicine. 5(4):332-337, July/August 2003. Accession Number:

00125817-200307000-00010

- Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, Rizo C, Stern A.

Health related virtual

communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects

of online peer to peer interactions BMJ, May 2004; 328: 1166.

- Eysenbach, G., & Diepgen, T. L. (1998).

Responses to unsolicited patient email requests for medical advice on the World

Wide Web. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1333–1335.

Accession Number: 00005407-199810210-00029

- Klemm, P, Bunnell, D, Cullen M, Soneji R, Gibbons P, Holecek A.

Online Cancer Support Groups: A Review of the Research Literature. CIN:

Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 21(3):136-142, May/June 2003.

Accession Number: 00024665-200305000-00010

- Kalichman, Seth C. 1,2,3. Benotsch, Eric G. 2. Weinhardt, Lance 2. Austin,

James 1,2. Luke, Webster 1,2. Cherry, Chauncey 1,2.

Health-Related Internet Use, Coping, Social Support, and Health Indicators in

People Living With HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 22(1):111-116, January 2003. Accession

Number: 00003615-200301000-00014

- Gardner DM, Mintzes B, Ostry A.

Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising in Canada: permission

by default? CMAJ. 2003 Sep 2;169(5):425-7.

- Review 20 abstracts from an annotated bibliography on

effectiveness of tailored communications

-

Suicide risk prediction through computer interviews.

-

Comparison of computer and interviewer administered assessments

-

Computerized health risk appraisal.

-

Computerized self assessment in psychiatry

-

Self administered psychotherapy.

-

Use of touch screens by patients.

-

Computers help patients decide about treatment

-

Examples

of online services

-

Read review articles

-

Health On Net (HON) Foundation's statistics

-

Regulation of drugs on Internet

-

Response to SARS

-

Patient use of the web

-

How broadband changes patients' pattern of use?

-

Which web site do people trust and why?

-

PEW's

report on search for health care information on the Internet

This page was organized by

Farrokh Alemi Ph.D. on

10/22/11 and last

revised on 10/22/2011.

This page is part of the course on

Electronic

Commerce & Online Market for Health Services.

|